|

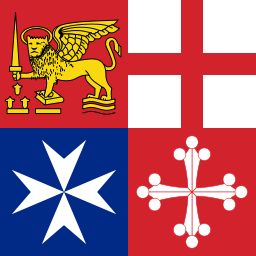

The Crest of the Italian Navy has the coat of arms of the four main maritime republics. Clockwise from the top-left: Venice, Genoa, Pisa, Amalfi. The four most successful Maritime city-states were Amalfi, Pisa, Genoa, and Venice. Amalfi was perhaps the first to establish itself, but it was also the most short-lived, being conquered by the Normans in 11th Century. With Norman control over Southern Italy firmly established, Mediterranean trade began to be controlled by the city-states of Northern Italy. The city-state of Pisa rose to prominence in the Western Mediterranean and the city-state of Venice developed into a superpower in the Adriatic. (See map 1 - 1090 AD) Pisa took control of the islands of Corsica and Sardinia, and took a lead role in many successful raiding expeditions against Muslim cities in Tunisia and the Balearic Islands. Meanwhile, Venice began to acquire many of the islands in the Adriatic as important stepping stones along the trade route to the Eastern Mediterranean. The Fourth Crusade The onset of the Crusades opened up many new markets for these maritime states in the East. In exchange for providing the ships necessary to transport the Crusaders to the Holy Land, the Italian city-states were given exclusive trading rights, tax privileges, and, in some instances, territorial control of strategic trade posts and islands along important trade routes. A prime example of this can be seen in the role of Venice during the Fourth Crusade. (See map 2 - 1215 AD) Originally, Venice had agreed to provide the ships for the Fourth Crusade, however a large number of the Crusaders did not show up in Venice and those that did lacked the funds to pay the full cost of the ships. The cunning Doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo, took this opportunity to accept as payment the assistance of the Crusaders in besieging the city of Zadar in the Adriatic. The crusaders agreed and the siege was a success. However the Crusaders were still low on manpower and funds when another new opportunity emerged: the Byzantine Emperor Isaac II had recently been deposed by his brother, Alexios III. If the Crusaders would stop off in Constantinople on route to the Holy Land to assist in restoring Isaac II to the throne, Isaac would agree to fund the Crusaders generously and also send Byzantine troops on the Crusade. Again the Crusaders agreed to take this detour and successfully completed the mission. However, Isaac II never sent the promised funds or the military assistance. This angered the Crusaders such that they sacked the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, deposed the Byzantines and established a "Latin Empire" and partitioned many of the former Byzantine territories amongst their allies, including Venice, which received Crete, Euboea, and the many of the Greek islands in the Aegean. Much of the Byzantine aristocracy was able to flee Constantinople and establish three Byzantine Successor States in the most far-flung territories of the Empire: Trebizond, Nicea, and Epirus. (See map 2 - 1215 AD) Eventually the Byzantines of Nicea were able to defeat the Latin Empire and re-establish Constantinople as their capital. They never recuperated the island territories from Venice however, and they never recovered to their former glory, instead they were gradually overrun by the Ottoman Turks from the East. The Rise of Genoa Towards the end of the 13th Century, the power of Pisa began to be supplanted by that of Genoa. Genoa had originally collaborated with Pisa in driving the Saracens out of the Mediterranean, but soon they became rivals for control over the islands of Corsica and Sardinia. Genoa entered into a shrewd alliance with the Crown of Aragon. This meant that when Aragon conquered the island of Sicily in 1282, Genoa was granted free trading rights. The contest between Genoa and Pisa for the island of Corsica culminated in the naval battle of Meloria in 1284. Pisa was decisively defeated, resulting in Genoa being the major naval power in the Western Mediterranean. (See map 3 - 1300 AD) Genoa also began to rival Venice for control of trade routes in the Eastern Mediterranean. After Venice had assisted the Crusaders in sacking the Byzantine capital and establishing the Latin Empire (see map 2 -1215 AD), Genoa opted to ally with the Byzantine successor states. This meant that when the Byzantines did recapture Constantinople in 1261, they granted Genoa free trade rights and a number of important trading posts and islands in the Aegean, such as Chios and Lesbos. Genoa then expanded her influence into the Black Sea, conquering important trading cities in the Crimea connecting the Mediterranean World with Russia, such as Caffa and Cembalo. (See map 4 - 1400 AD) As the power of the Byzantine Empire began to be supplanted by that of the Ottoman Turks, the Genoese lost their main ally in the Eastern Mediterranean. A long war with Venice culminated in the Battle of Chiogga in 1380, the Genoese Fleet was destroyed and, thereafter, Genoa went into a slow decline. Wars with the Ottoman Turks The Ottoman Turks were a Turkish dynasty that rose to prominence by conquering many of the territories of the decaying Byzantine Empire. By 1400, the majority of the Byzantine territories in both mainland Asia and Europe were under Ottoman Turkish control. In 1453, the Byzantine capital of Constantinople was conquered, bringing an end to the Byzantine Empire. The Ottomans immediately transferred their capital to Constantinople and renamed it Istanbul. At first the Ottoman Turks were primarily a land empire. However after the conquest of Constantinople, the Ottomans began to contest control of the Mediterranean Sea with the Christian maritime republics, particularly Venice. Venice was sourly defeated by the Turks at the Battle of Zonchio in 1499. Thereafter, slowly but surely, the Turks began to conquer the territories of Venice and Genoa in the Eastern Mediterranean. Genoa lost the island of Lesbos to the Turks in 1462, and the islands of Samos and Chios in 1566. (See map 5 – 1500) Venice lost Cyprus to the Turks in 1571 and over the course of the next 150 years, the Turks would conquer most of her Greek possessions. The Turks were however stopped from expansion in the Western Mediterranean at two important battles: firstly, the failed siege of Malta in 1565 where the Knights Hospitaller defeated the Ottomans, and secondly, at the Battle Of Lepanto in 1571, where the so-called "Holy League", an alliance of a number of Christian forces, including both the Republics of Venice and Genoa, defeated the Ottomans in the Gulf of Pastras, off the west coast of Greece. (See map 6 - 1575). Trade shifts from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic As the Ottoman Turks continued to close off trading opportunities in the Eastern Mediterranean, Europeans increasingly sought out an alternative route to the East via the Atlantic, the idea was to sail around the entire continent of Africa to reach India and beyond. A successful sea route via the Atlantic would inevitably lead to new economic opportunities for the Atlantic facing nations of Europe at the expense of the maritime republics of Italy. To a certain extent, the maritime republics helped to foster their own decline by their continuous advances in maritime technology, their pioneering interests in trying to find an Atlantic Sea route to the Orient, and their financing of the Atlantic sea voyages of Spain and Portugal. As early as the 13th century, the Genoese were exploring the Atlantic and looking for a sea route to the Orient. In 1291, the Vivaldi brothers of Genoa set out on just such a mission but vanished without a trace. 21 years later, another Genoese sailor, Lancelotto Malocello, went searching for their fate but only reached as far as the Canary Islands. The island of Lanzarote in the Canaries is in fact named after him. It would take European ship-builders another 100 years to design the kind of vessels that could cast out into the unconfined waters of the Atlantic with relative safety and it was the Atlantic facing Portuguese, not the Italians, that would lead the way. Nevertheless, the early Atlantic explorations would continue to be strongly influenced by the entrepreneurial spirit of the Italian city-states. Whilst there is some debate as to the true origin of the great explorer Christopher Colombus, most accept that he was from Genoa. Amerigo Vespucci, the explorer for whom the continent of America is named after, was also Italian: from the Republic of Florence. But most importantly, it was the Genoese bankers that financed many of Spain's early expeditions across the Atlantic to the Americas. Fernand Braudel even called the period 1557 to 1627 the "age of the Genoese". |